But when you notice that it is vast, you should be happy; for what (you should ask yourself) would a solitude be that was not vast; there is only one solitude, and it is vast, heavy, difficult to bear, and almost everyone has hours when he would gladly exchange it for any kind of sociability, however trivial or cheap, for the tiniest outward agreement with the first person who comes along, the most unworthy. . . But perhaps these are the very hours during which solitude grows; for its growing is painful as the growing of boys and sad as the beginning of spring. But that must not confuse you. What is necessary, after all, is only this: solitude, vast inner solitude. To walk inside yourself and meet no one for hours––that is what you must be able to attain. (Rainer Maria Rilke. Letters to a Young Poet. Trans. Stephen Mitchell. NY: Modern Library, 2001, p. 53-54).

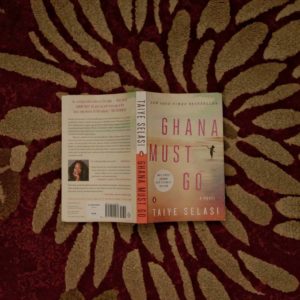

According to the American Heritage Dictionary, Solitude is “the state of being alone” or “a lonely and secluded place.” But solitude as a state outside company does not satisfy Rilke’s definition. Especially when one considers today, the attacks made on one’s attention from every little nook and cranny under such labels as the news, social media, etc. For instance, deleting my Facebook account was not so difficult and not being on social media constantly is something I actually enjoy. But I suffer an email addiction as well as a YouTube addiction! Now tell me, how can one possibly encounter no one on YouTube for hours? That is, how can one possibly claim to be in solitude whiles one’s eyes are heavily glued to their computer? In his 1836 essay, “Nature,” Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote:

To go into solitude, a man needs to retire as much from his chamber as from society. I am not solitary whilst I read and write, though nobody is with me. But if a man would be alone, let him look at the stars. The rays that come from those heavenly worlds, will separate between him and what he touches. One might think the atmosphere was made transparent with this design, to give man, in the heavenly bodies, the perpetual presence of the sublime.

I think I have experienced that heaviness that Rilke defines as a successful state of solitude and I think this state is popularly identified as loneliness. It is as silent as a barren desert, and sings like a virgin forest. One of the best examples of solitude in this sense that I can recall coming across in literature is in J.P. Jacobsen’s Niels Lyhne (1919), in the description of the megalomaniac character, Mr. Bigum:

Yet there were other times when the solitude of his greatness weighed upon him and depressed him. Ah, how often, when he had communed with himself in sacred silence, hour after hour, and then returned again to consciousness to the audible, visible life around him, had he not felt himself a stranger to its paltriness and corruptibility. Then he had often been like the monk who listened in the monastery woods to a single trill of the paradise bird and, when he came back, found that a century had died. Ah, if the monk was lonely with the generation that lived among the groves he knew, how much more lonely was the man whose contemporaries had not yet been born. In such desolate moments he would sometimes be seized with a cowardly longing to sink down to the level of the common herd, to share their low-born happiness, to become a native of their great earth and a citizen of their little heaven. But soon he would be himself again. (28)

Every choice human being strives instinctively for a citadel and a secrecy where he is saved from the crowd, the many, the great majority––where he may forget ‘men who are the rule,’ being their exception––excepting only the one case in which he is pushed straight to such men by a still stronger instinct, as a seeker after knowledge in the great and exceptional sense. Anyone who, in intercourse with men, does not occasionally glisten in all the colors of distress, green and gray with disgust, satiety, sympathy, gloominess, and loneliness, is certainly not a man of elevated tastes; supposing, however, that he does not take all this burden and disgust upon himself voluntarily, that he persistently avoids it and remains, as I said, quietly and proudly hidden in his citadel, one thing is certain: he was not made, he was not predestined, for knowledge. If he were, he would one day have to say to himself: ‘The devil take my good taste! but the rule is more interesting than the exception––than myself, the exception!’ And he would go down, and above all, he would go ‘inside.’ (37)

I can see Mr. Bigum disagreeing with Nietzsche’s point of view and I am not myself sure I understand him exactly. But I am intrigued by his notion of going inside. If by going inside he means going down amongst the seemingly common while deeply stationed, consciously, within one’s values or idea of self, then another interesting perspective that gives both Nietzsche and Rilke’s thoughts good prodding is again that of Emerson’s. In his 1841 essay, “Self-Reliance,” Emerson says, “It is easy in the world to live after the world’s opinion; it is easy in solitude to live after our own; but the great man is he who in the midst of the crowd keeps with perfect sweetness the independence of solitude.” Thus Emerson agrees with Jacobsen that solitude––outside company––can become comfortable, and with Nietzsche that solitude is easier than facing society. But solitude is even more challenging to contain when carried into company. For it makes one solitary in environs where the solitary is often ridiculed and shunned as she represents the uncomfortable and thus the unpopular.

Emerson’s understanding of solitude as an internal state that proceeds through society, unflinchingly, fits in with Rilke’s concept how? I think the connection is in the precursor of the passage, “there is only one solitude, and it is vast, heavy, difficult to bear.” In that solitude is really always the same, in that it is a vastness,––not a simple instance?––or perhaps a wilderness that is boundless in that it is heavy upon the shoulders that would carry it rather than accept to merge with it. Here lies the similarities: in whatever form it comes upon one the vastness of its solitariness is same. For where it is difficult to bear––i.e., solitude outside company for Rilke––others have found it enjoyable but found the same challenge elsewhere––i.e., within company for Jacobsen. Nietzsche adds further to this, again from Beyond Good and Evil, in saying:

Independence is for the very few; it is a privilege of the strong. And whoever attempts it even with the best right but without inner constraint proves that he is probably not only strong, but also daring to the point of recklessness. He enters into a labyrinth, he multiplies a thousandfold the dangers which life brings with it in any case, not the least of which is that no one can see how and where he loses his way, becomes lonely, and is torn piecemeal by some minotaur of conscience. Supposing one like that comes to grief, this happens so far from the comprehension of men that they neither feel it nor sympathize. And he cannot go back any longer. Nor can he go back to the pity of men. (41-2).

Perhaps one can say then that, solitude, though perceived differently in varying situations, still makes identical demands and discharges similar challenges for all who encounter it. It is, in a sense, a wilderness that empties being. An independence that insists on freedom from even that which it offers itself to. Solitude, then is that which demands and prefers its own emptiness. It is a weight when one insists on harboring it rather than having it dispel one. It is a joy when one is able to surrender to it, yet in coming back to self, one suffers the weight of one’s self in its absence. And hence Rilke’s advices, “But when you notice that it is vast, you should be happy…What is necessary, after all, is only this: solitude, vast inner solitude. To walk inside yourself and meet no one for hours––that is what you must be able to attain.” The common thread, then, is that solitude is not for the one who cannot give up herself, for one does not go into solitude to meet anything but solitude. One does not even go into solitude one becomes solitude.

—

Jane A. Odartey

Pingback: Musings: On Humility - Jane Through the Seasons by Jane A. Odartey

Pingback: 2022, Bye-bye! - Jane Through the Seasons by Jane A. Odartey