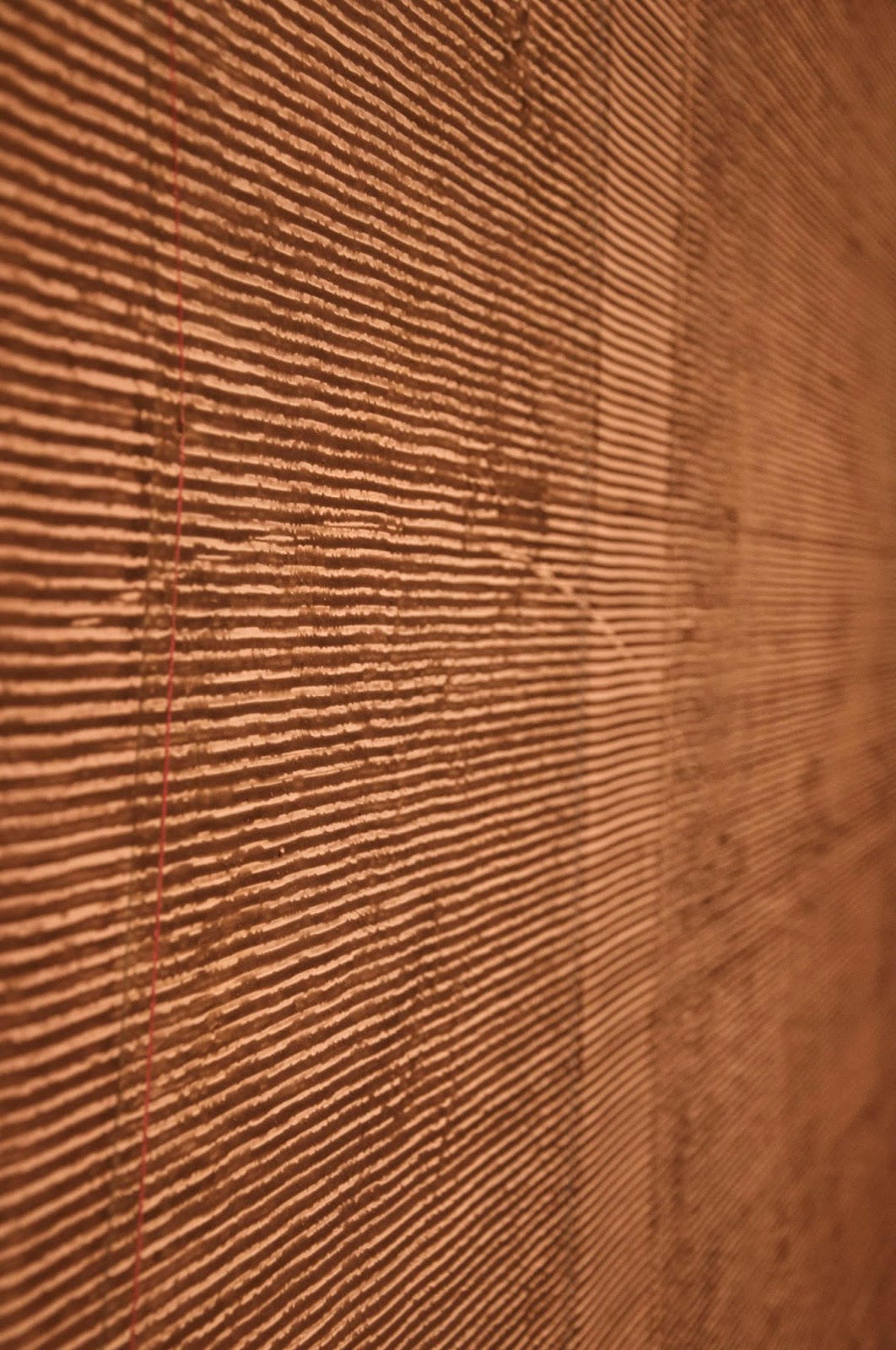

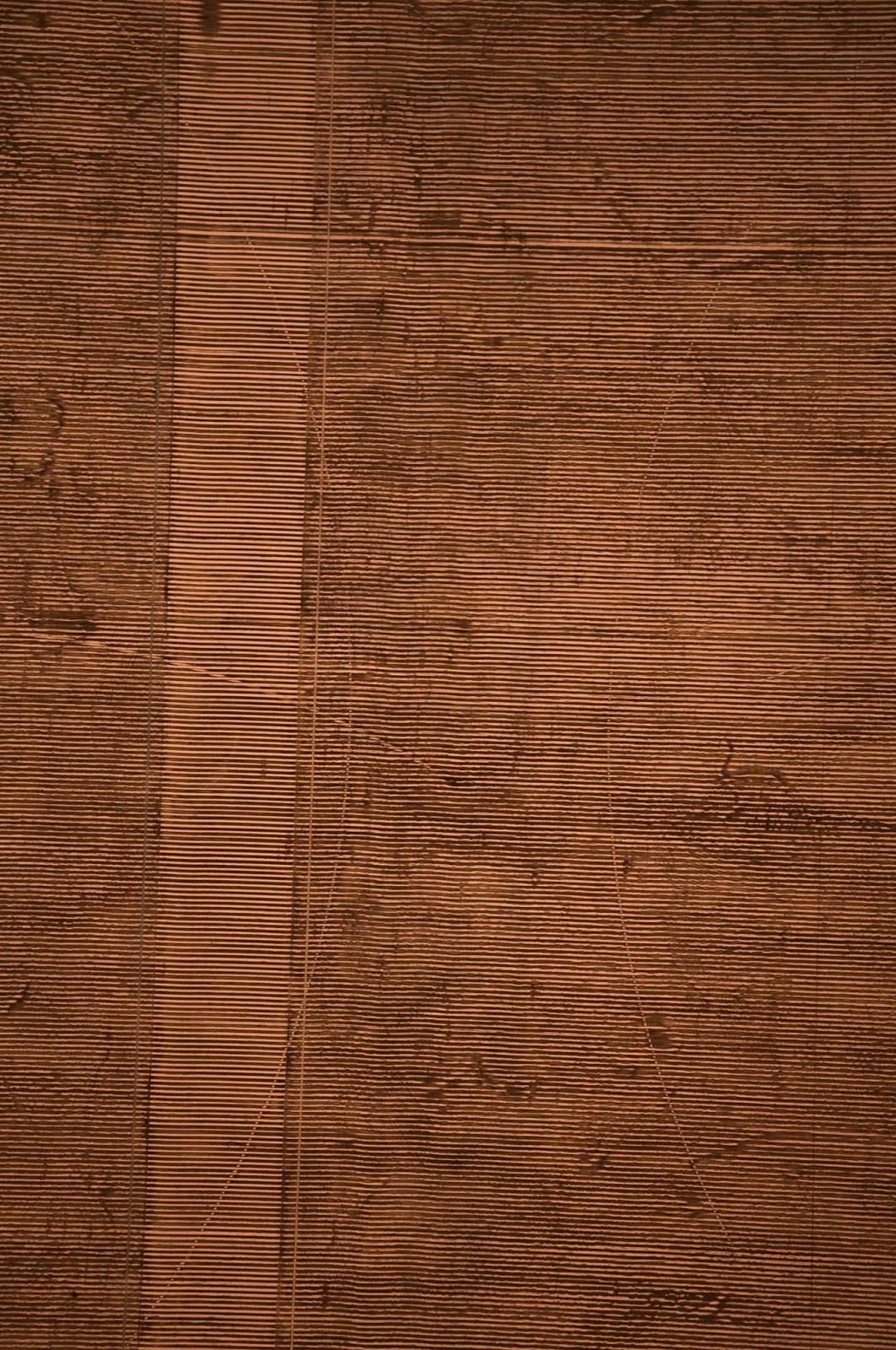

Amongst several wonderful artworks on display in one of few current exhibitions at the Studio Museum in Harlem, Circa 1970 (Nov. 17, 2016 – April 2, 2017), my favorite is the great abstract work, Khee I, 1978, by Jack Whitten. Every time I walk into the gallery I am drawn to and into the beautiful abstract painting. It excites so much, say so much, say so little: fibs beautifully and seems sincerely cruel. Leaving one to decide whether to take it whole or just the part that feels favorable. I have been struggling to choose, but yesterday, as I sat in front of it––during my lunch hour––to try to find the words to write of it, I finally came to accept it whole and I believe now it speaks no lies, just truths. It is I who went to it and tried to tell it to be either or. Its sharp countless steep horizontal gullies––sharply rising terrace-like etchings––leading only into itself is at the same time a flat surface with minimal texture. In one instance it is everything complex, unique, and wondrously intriguing; and yet it appears also to be a mere mundane image of dull gray-tan horizontal lines and few––seemingly purposeful yet self-mocking in their meaninglessness, or perhaps shy secretiveness, or sagely taciturnity?––vertical lines of pink and blue.

There is a freedom to the work that is the work itself and it, that is the untrammeled work, seems eager to pour itself into the eyes that open, without restraint, to it. It seems so eager to give everything to the viewer and yet it is unable to. Not because it cannot give but because the viewer does not know how to take it. Its fervent generosity brought tears to my eyes. Its song is a tune of patient solitude: happy to be, happy to give, happy to wait, happy to be rejected. In its simplest form, one would say it is black and white. Oh but it is not black and white: It is that which knows itself to contain everything and nothing. It is that which exists as it ought to.

I know the pictures here do it very little good. For it is difficult to capture through photographs the heartbeats of this painting. It arouses in one, one’s naturalness and laces its fine-rough simplicity into the vulnerable form, which is then depicted to be all strength. And in being just there it shows the peace of surrender: exudes the music of peace. Thus grows beautiful and beautiful in every moment the eyes fixate on it. Yet when one tears away, one feels it wholeness still within. As if it had never not been there.

This weathered vertical landscape defies all busyness with limitless patience. Its scars, its beauty marks: that which moves one the more––antidotes to tumultuous agonies. A smooth/rough ocean of soft/hard rock that is only acrylic on canvas. But what is only? What is illusion? So seems its stance, emitting a sublimeness that is beguiling and fondly bewitching. It shows itself to one as though one is a tiny speck viewing its grandness from afar, and yet so very close, at its heart.

About it, seemingly at distance, swirls transparent smokes of soft powdered yellows, pinks, and blues lyrically. The colors dancing into its warm gray-tans, yet never dissolving into them. Transparent permanent vapors––ghostly nymphs in play?! One is uncertain if one’s eyes see what they seem to say they envision. But your heart speaks for both itself and mind, if you listen closely enough and you believe in the ivory whites and warm grays that seem to have been dyed by a wisdom impossibly further, and yet closer to your grasp, you start to breathe as the painting does, you start to see your reflection in its numerous etches and start to remember its freedom and its awesome generosity.

—

Jane A. Odartey