In a setting of New York in the early 1870s, Newland Archer, a member of the old affluent class of Fifth Avenue is about to head to the Academy of Music to see a performance of Faust. But his thoughts are mostly on May Welland, anticipating the announcement of their engagement. Newland, Edith Wharton’s main character in The Age of Innocence, is mostly the narrator of the novel. Despite his belief that he is less conservative than the majority of his class, it is only when he falls passionately in love with his fiancée’s cousin, the Countess Olenska, that he realizes he had not lived as liberally as he believed. The novel discusses love, traditions, family, and the duties such ties demand of one. But The Age of Innocence is really a love story, my favorite sort, the unrequited kind. However what I find most fascinating about the novel is the feminine perception of the masculine perspective on the female. In other words, Edith Wharton explores the masculine ideology of women in the 1870s through Newland. Archer’s views on women being more heavily founded on stereotypes rather than his own rich observations, seem to not truly grasp the ingenuity of the women in his life; May Welland’s especially.

One may argue that it was not Newland who decided that May would make him the perfect wife, it was his little society. As his mother voiced out in agreement; “There was no better match in New York than May Welland, look at the question from whatever point you chose” (28)*. And if Mrs. Archer knew this, one may argue that May knew it, too. But what is not said, although implied is that Newland is equal, if not superior to May on the marriage market. The Age of Innocence is heavily infused with implications. Newland’s whole theory on May is that he can actually read her mind. On his love for May it is said that; “The young man was sincerely but placidly in love. He delighted in the radiant good looks of his betrothed, in her health, her horsemanship, her grace, and quickness at games, and the shy interest in books and ideas that she was beginning to develop under his guidance” (34). Thus Archer’s love for May is centered, “placidly,” on all that she has been taught to display in ways that would catch his attention. Based on some quotes that I will provide throughout the rest of this review, it seems that May plays an even bigger part in becoming Newland’s wife than Newland understands. One of the earlier signs of this suspicion is the photograph that May gave Archer of herself during their courtship:

As he dropped into his armchair near the fire his eyes rested on a large photograph of May Welland, which the young girl had given him in the first days of their romance, and which had now displaced all the other portraits on the table. With a new sense of awe he looked at the frank forehead, serious eyes and gay innocent mouth of the young creature whose soul’s custodian he was to be. That terrifying product of the social system he belonged to and believed in, the young girl who knew nothing and expected everything, looked back at him like a stranger through May Welland’s familiar features; and once more it was borne in on him that marriage was not the safe anchorage he had been taught to think, but voyage on uncharted seas. (32)

Although Newland’s look on marriage here is insightful, do consider the size of that photograph. The size of things speak, and this large photograph foreshadows the role May wished to play in Newland’s life. It is noteworthy that Newland’s focus is not a contemplation of the subtle details but the obvious ones. So he pays attention to May’s youth and innocence. Which makes one wonder if Newland sees anything other than the feminine ideology that he has been imbued with. It is suggested in his ability to discern that although May’s feature’s are familiar, her genuine character is unknown to him. And if he had taken the time to try to discover who May is rather than returning always to the ready-made notion that she is “young and innocent,” he might have realized that innocent-looks do not always signify innocence. And innocence can be staged. But perhaps Archer thought he needed May to be innocent. This perspective is visible in his thoughts as he watched May’s reaction to a scene in Faust where M. Capoul tries to persuade Madame Nilsson to become his lover:

“The darling!” thought Newland Archer, his glance flitting back to the young girl with the lilies-of-the-valley. “She doesn’t even guess what it’s all about.” And he contemplated her absorbed young face with a thrill of possessorship in which pride in his own masculine initiation was mingled with a tender reverence for her abysmal purity. (6)

This “thrill of possessorship” and the pride it ejaculates to the ego of his masculinity is what Newland is trained to seek, and what May is trained to ignite. But that May is more than she seems is conceivable through her own mother, and better yet her grandmother:

He knew, of course, that whatever man dared (within Fifth Avenue’s limits) that old Mrs. Manson Mingott, the Matriarch of the line would dare. He had always admired the high and mighty old lady, who, in spite of having been only Catherine Spicer of Staten Island, with a father mysteriously discredited, and neither money nor position enough to make people forget it, had allied herself with the head of the wealthy Mingott line, married two of her daughters to “foreigners” (an Italian marquis and an English banker), and put the crowning touch to her audacities by building a large house of pale cream-colored stone (when brown standstone seemed as much the only wear as frock-coat in the afternoon) in an inaccessible wilderness near the Central Park. (10)

How can Newland know this of May’s lineage and still feel that what he sees of her reveals much of what is not visible to him? Consider, for instance, that scene in the novel where Newland kisses May on the bench in St. Augustine:

They sat down on a bench under the orange-trees and he put his arm about her and kissed her. It was like drinking at a cold spring with the sun on it; but his pressure may have been more vehement than he had intended, for the blood rose to her face and she drew back as if he had startled her.“What is it?” He asked, smiling; and she looked at him with surprise, and answered: “Nothing.” (106)

How can it be “nothing,” it is indeed something. May has learned something that she did not anticipate in Newland. And this is his passion; she was not expecting it. Her parent’s marriage, after all, is not a passionate one. Her immediate and most frequent lessons on marriage is that the man must be infantilized and treated delicately; that the husband would require much attention and care, but surely not passion, too! If this reasoning holds any truth, it makes sense why May suddenly wants to know if Newland is still involved with his lover. Perhaps she realizes that she would not be able to satisfy the passion she has discovered in him. But recall that May is the girl who sends the large photograph of herself. She wants to be the center of Newland’s world, hence she wouldn’t want any other lovers lurking about. And if Newland was as observant as he thought himself to be, the opening to the question of whether or not he still holds a torch for his old lover, whom May very well knew was already married to another man, would have alerted him to her ability to act differently than she felt:

She dropped back into her seat and went on: “You mustn’t think that a girl knows as little as her parents imagine. One hears and one notices––one has one’s own feelings and ideas. And of course, long before you told me that you cared for me, I’d known that there was some one else you were interested in; every one was talking about it two years ago at Newport. And once I saw you sitting together on the verandah at a dance––and when she came back into the house her face was sad, and I felt sorry for her; I remembered it afterward, when we were engaged.” (111)

This was all Archer needed, to know that his fiancée had things going on in that “young” and pretty head of hers that he has no clue about. His answer here, refuted there being, any longer, anything between him and the woman to whom May alluded. But one wonders if May did not notice that she is herself different from this woman, and whatever it is that attracted Archer to the latter is not present in herself? And one wonders the relationship between her daring to reveal to Archer her thoughts and her new understanding of Archer, owing to their kiss on the bench.

Before the St. Augustine incident, when Archer had delayed his routine of sending her flowers in the morning, May notices and was sure to not complain. Instead she wittily reminds him that even though it was not an original idea, for it has been the same for Gertrude Lefferts––whose husband, everyone knew, was engaged in several affairs––when she was engaged, and her flowers came every day on time (61). There are a few insightful clues in this little scene that I will leave you to find for yourself. But now, tell me this is not a brilliant mind at work?! Also when Newland mentions that he “saw some rather gorgeous yellow roses and packed them off to Madame Olenska” (61), one could almost see May’s mind at work, for I have already proved, I hope, that she notices and remembers details. It seems this intelligence, that poor Newland, never suspects in pretty and young May is the reason why he gets what he only realizes at the last minute that he does not want, marriage to May. And it is for the same reason why Ellen also gets a telegram from May when her parents consents to her early marriage to Archer. Somehow she manages to reduce a year’s wait to a month’s when she had been insisting that traditions must be honored and there was no reason to rush. So who did she rush the wedding for? Herself or Archer?

The question then is how long had May suspected that Newland desired Ellen? Did she not think, then later learn, that Ellen had more in common with Newland’s lover? Consider earlier on in the novel when Newland joins May in her family’s box and meets Ellen for the first time since her return. Newland asks if May had told Ellen about their engagement and she replies saying, “Tell my cousin yourself: I give you leave. She says she used to play with you when you were children.” To which Ellen replies without waiting for Newland to speak, “We did used to play together, didn’t we? She asked, turning her grave eyes to his. “You were a horrid boy, and kissed me once behind a door; but it was your cousin…who never looked at me, that I was in love with” (14). If May knew that Newland had a crush on Ellen when they were younger, she does not reveal it. She only mentions the innocent part. Just like she says “nothing” when Newland notices her discomfort after he kissed her.

Of course, one cannot be surprised that May was certain to let Ellen know that she was expecting a baby, even before she was certain that she was actually having a child, and even before Archer learns of it. Thus giving Ellen all the reasons she needed to leave New York for Paris. But if you really doubt May’s incredible intelligence, you must consider the farewell dinner party she throws for Ellen. She insisted that the first party she and Newland host as a married couple––in the home they mean to raise their family––should be a goodbye event for her dear and poor cousin Ellen. The sort of kindness coming from a woman like May is like sticking out a perfectly manicured middle finger to a woman like Ellen. An insult that earns May the respect and sympathy of her society and makes sure that, Ellen, if she had any conscience at all, which she does––as May well knows––will leave Newland alone. Brilliant!

My favorite character in the novel is May, of course. I mean I do love Ellen, but she acts as she feels, and one senses that she is an abyss of sorts; there is no point trying to read her. It is May who gets you pausing, and reflecting because she is something of a packaged puzzle, and you are given the pieces to put her together. She is presented as this simple minded woman who does not know what she wants, but she, unlike Ellen and Newland, knows exactly the kind of life she wants: wife, mother, routines, rituals, and no surprises. And she had the skills and knowledge to make sure she gets things exactly as she desired.

By narrating through the perspective of Archer, Edith Wharton shows how even the seemingly liberal man of the 1870s underestimated what was deemed the innocent woman of the time. In William Lyon Phelps’ review of the novel, included in my edition, he defines Wharton’s theory of innocence as choosing one’s duty over the summons of that wicked disease of falling in love with the wrong person. According to Phelps, if Ellen and Archer were to flee, the book would become Anna Keranina. I think Phelps to be right, but I think what Wharton achieves is just as invigorating. Wharton, in her portrayal of innocence seemed to be asking what is it? rather than this is it! And the innocence alluded to in May Welland’s character is part the mixture engineered by a society and the ingenious performance of a woman who understood the rules and knew how to work them to her favor.

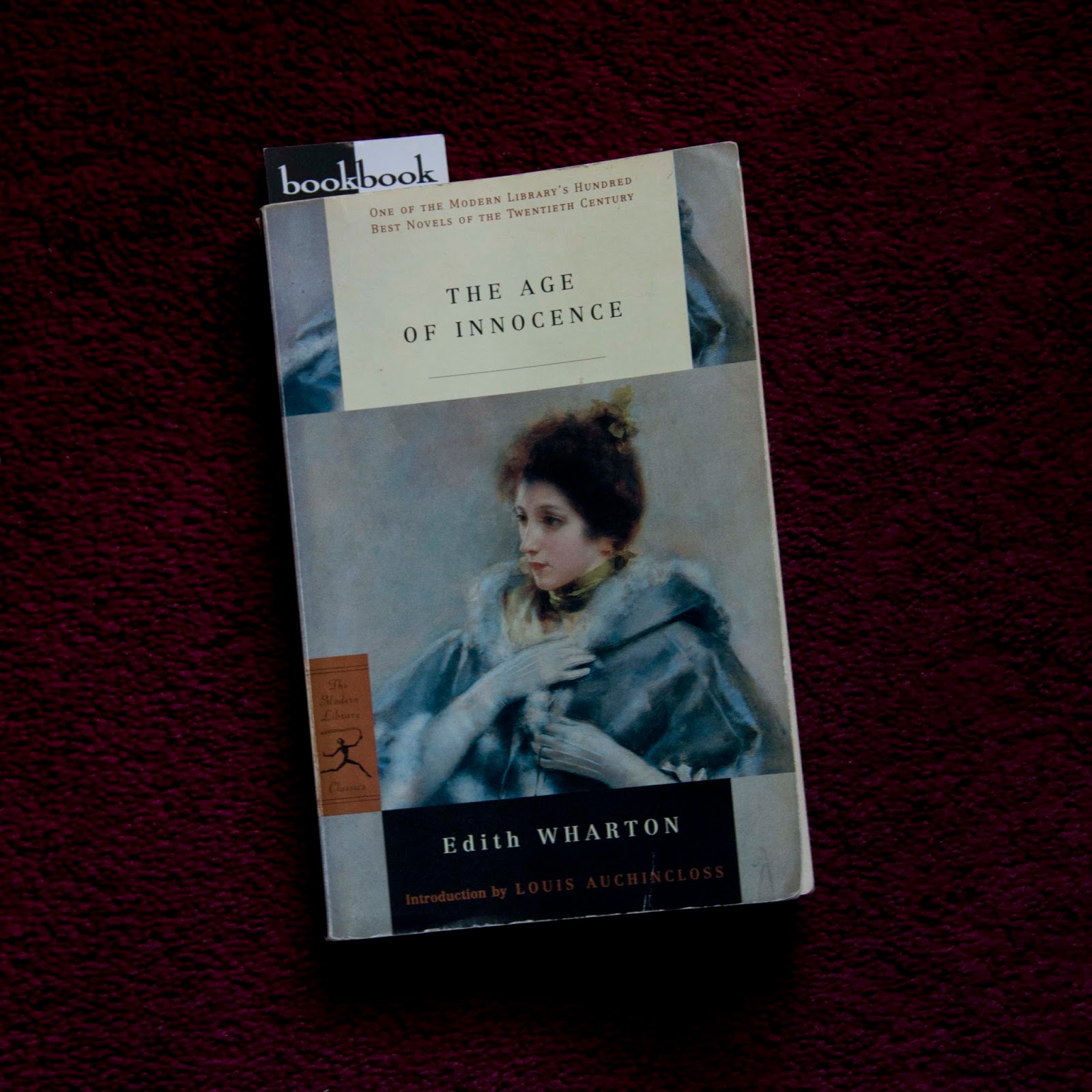

*Wharton, Edith. The Age of Innocence. New York: Modern Library, 1999. Print.

—

Jane Odartey